Recently, a Turkish research group [1] argues that despite significant progress towards sustainable cosmetics, mass-produced sustainable packaging has proven to be a challenge. The complexity of environmental, economic, social, technological, and policy considerations, along with varying consumer behaviors and corporate goals, makes it difficult to select an optimal strategy across heterogeneous supply-chain components worldwide. Meanwhile, the cost and effort of developing, testing, and validating alternative strategies discourages empirical exploration of potential alternatives. In this article, Pierre Trinh, sustainability researcher at The Skynth, will review those complex challenges and, whenever possible, suggest sustainable initiatives to overcome the market-based problems the world is facing.

What is the problem with cosmetic

packaging?

Since the 1970s, the cosmetics industry [2] has faced concerns in terms of health, environmental impact, and animal testing, including for its packaging sector. Caruana, from the University of Twente, mentioned that popular brands typically do not offer sustainably-packaged color cosmetics, leading to “consumer helplessness in this regard and a belief that changes should be led by cosmetics producers and government regulatory action.” [3]

Therefore, it is important to learn from the variety of reliable literature that has been accumulated in areas of environmental protection strategies and sustainable packaging to identify promising directions as well as potential pitfalls.

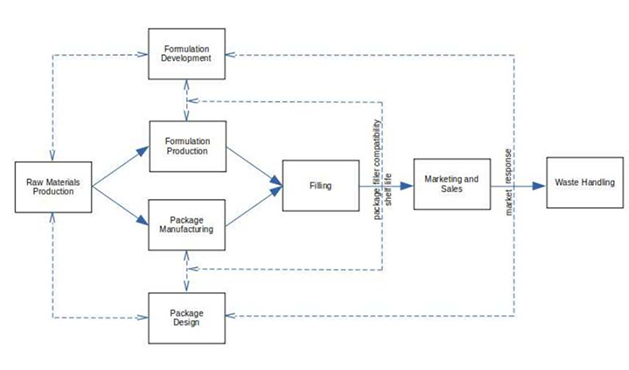

First, we need to understand a typical process of conventional cosmetic manufacturing.

It begins with concept and design around the brands targeted audience and product being produced, while keeping an open communication with manufacturers, so formulation development can meet specific targets while selecting ingredients that are safe for skin application, such as surfactants, preservatives, colorants, and exfoliators. This is followed by ingredient sourcing, batching and mixing to create a base and disperse any pigments, which is regularly supervised by a quality control team to make sure the product will pass the quality testing. Once this is done, packaging and a final quality control take place, and once approved, distribution is processed.

Although in theory seems safe, almost every step in cosmetic manufacturing impacts sustainability at an environmental, social, and economic level. In tradition, packages are designed based on customers’ specific demands in terms of shape, size, color, etc. Packaging production is typically outsourced, while raw materials flow from suppliers to packaging producers. The product is then filled, distributed, and commonly traded without any consideration of the end-of-use stage.

Packaging materials play a crucial role and can vary depending on the brand, the product formulation, quality, and availability. Most cosmetic products are still distributed in plastic packaging, considering its flexibility, good strength to protect the cosmetic products, and a cheaper alternative; nevertheless, this is the critical issue sustainability practices are trying to eradicate; although not easily substitutable, these remain the number one threat to biodiversity and pollution. Although several global initiatives have been developed by recognized brands to decrease their usage, in most companies, feedback at any stage is related to quality issues and delivery schedules. Each stage represents a set of activities and potentially global supply chains.

Multiple companies may supply materials and parts to a packaging manufacturer, who may also outsource several production steps. Depending on their business models, many cosmetics companies regularly add new products, while others may not. Although the materials and manufacturing processes are well-understood, attempts to change packaging materials based on customer demand or cost considerations can be problematic.

Therefore, even if the consumers appeal for sustainable options, the manufacturers have no consistent incentive to achieve those, urging the needs of an innovative process.

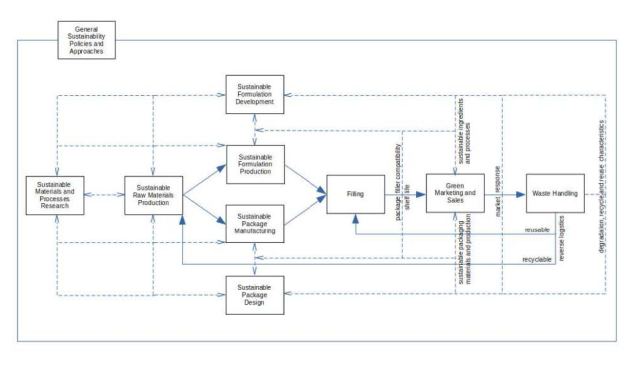

A circular business model is a commonly employed system by businesses attempting to reduce the environmental impact manufacturing brings, going around the typical linear models based around getting resources → making products → selling them → throwing them away when they are no longer usable, while circular business will go in a full circle, maximizing resources and forcing the manufacturers to make products sustainable enough to maintain it [4]. In order to develop circular business models, processes and products need to be redesigned and harmonized across the supply chain in view of sustainability regulations and frameworks [5].

Meanwhile, novel packages, formulations, and additives are some of the concerns that must be validated for compatibility in terms of functional requirements such as their shelf life, health, and environmental impact, further focusing on the waste-handling infrastructure [6][7].

A transdisciplinary framework is important for the circular bioeconomy with increasing digitalization and technological convergence. Cross-industry innovation is a significant part of open-source development, including for areas such as cosmetics, personal care, chemicals, and plastics. Still, it is essential to see opportunities and challenges while operating such an innovative process.

Analysis

Which factors/elements are related to the sustainability of ingredients used in cosmetics packaging?

Sustainable cosmetics packaging needs to move beyond being a theoretical consideration to have a meaningful environmental impact; policy and corporate decisions regarding the optimal strategy rely on an ability to estimate their outcomes, and empirically validated models based on these theoretical considerations are key towards implementing effective change.

The goal is to develop a package that meets the expectations of both consumers and producers, and so re-engineering the supply chain requires extra input from the areas shown in figure 3. Companies are beginning to get regulatory pressures for greener strategies in packaging, where glass and metal are the main materials considered for waste management, as they are minimalistic or otherwise reusable; however, companies still lack to convince and teach consumers on options to do this, causing a gap in the final goal. When it comes to sustainable production, the use of clean energy and modes of transport to reduce emissions in the packaging and distribution phases are essential elements that must be not only implemented but also reported. Large companies often omit their sustainable production efforts and how they impact their business operations in fear of lack of effort or criticism; nevertheless [8], transparency is crucial. Companies need to communicate their sustainability initiatives clearly to build trust and demonstrate genuine commitment.

It has also become necessary to emphasize that “natural” does not inherently mean safe and that a natural product is not necessarily safer than its chemical substitute [9]. “organic” and “green” are terms commonly interchangeable with “sustainability”, but they are not synonyms; while green cosmetics would mean they avoid any kind of synthetic ingredients in their formulation, sustainable ingredients are those addressing all dimensions to meet the current needs without compromising the future and are considered across all stages of the cosmetic creation [10]. This can include water consumption with waterloop factories, respecting biodiversity and disregarding any practice that increases the risk of deforestation and loss of habitat, and the vicious concern of obtaining produce from natural sources that, although seeming appealing for the consumer, can lead to a higher accumulation of greenhouse gases and an increment in the global temperature.

Current Potential Areas for Improvement.

Biodegradable plastics have been proposed as a solution to traditional petroleum-based polymers, while their degradation in marine environments has not been studied extensively [21]. The European Commission, in 2001, defined CSR as “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and their interaction with stakeholders”. While the market approach shifted to encouraging CSR with enthusiastic industry support, at least in part to forestall regulatory and legal interventions, growing realization changes would be needed in existing economic activities [22].

An integrated design strategy incorporating technical models at various scales, from molecular to macro-level, as well as process, product, consumer, and business models, is needed for emulsified cosmetic products.

- “Social marketing” to change human behavior;

“Demarketing” to discourage use of goods such as energy in times of shortage has also arisen; - “Critical marketing” reflects a criticism of marketing in general, including its existence;

- “Positive marketing” is all actions that create value for firms, customers, and society.

Meanwhile, ISO-16128 has been introduced as a means towards unifying some of the concepts but can create further confusion across jurisdictions, such as due to the inclusion of GMOs in natural products [23]. Furthermore, materials claimed to be 100% biodegradable were found to degrade approximately 8% in the digestive tracts of turtles, while in another study only four of the six materials claimed to be biodegradable actually turned out to be so, indicating misuse of the term.

CONCLUSIONS

A circular business model is a commonly employed system by businesses attempting to reduce the environmental impacts of cosmetic production, especially at the packaging stage. Although there are several potential benefits of applying this innovative model, a variety of challenges arise in material selection, production and packaging quality, supply chain management, waste management, and green marketing, urging the product developers and manufacturers to extensively focus on sustainable aspects of a product with a more holistic approach.

RECOMMENDATIONS

It is difficult to determine the optimal course of action, to implement it, and to monitor its effects, but a few things companies can do to improve the sustainability of their packaging include

- Implement energy and water efficiency measures: Optimizing energy and water use in manufacturing processes can significantly reduce operational costs and environmental impact simultaneously; companies can achieve this by installing energy-efficient equipment and systems, utilizing renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power, and implementing water recycling and reuse systems throughout the manufacturing process.

- Engage even more in post-consumer recycling and reuse: Developing systems for recycling and reusing post-consumer packaging is not enough to promote circular economy principles. Companies should set up programs for consumers to return used packaging, to not just recycle materials to produce new packaging, but try and close the social gap and dedicate time to educate their current and future customers and utilize waste materials for energy production that can be perfectly reconditioned to serve a different purpose. This approach can reduce landfill waste, conserve resources, and enhance sustainability efforts.

- Use sustainable sourcing for raw materials: Sourcing raw materials sustainably is crucial for reducing environmental impact, but companies should focus on using renewable and eco-friendly materials while conducting life cycle assessments (LCA) to evaluate the environmental impacts of their products, and especially partnering with suppliers that adhere to sustainable practices. The time spent attempting to select ethically source produce and stricter supervision won’t be useful if suppliers and manufacturing work does not adhere to their specific needs to remain useful and sustainable.

REFERENCES

[1] M. Dube & S. Dube (2023); Towards Sustainable Cosmetics Packaging; MDPI

[2] Kumar, S., Exploratory analysis of the global cosmetics industry: major players, technology, and market trends. Technovation 2005, 25, 1263–1272.

[3] Caruana, P., Ethical Consumerism in the Cosmetics Industry: Measuring How Important Sustainability is to the Female Consumer, University of Twente, The Netherlands, 26 June 2020.

[4] UCEM (2024); 5 circular business models (and how they can give you a competitive advantage)

https://www.ucem.ac.uk/whats-happening/articles/circular-business-model/

[5] Acerbi, F.; Rocca, R.; Fumagalli, L.; Taisch, M. Enhancing the cosmetics industry sustainability through a renewed sustainable supplier selection model. Production & Manufacturing Research 2023, 11(1), 2161021

[6] Cinelli, P.; Coltelli, M.B.; Signori, F.; Morganti, P.; Lazzeri, A. Cosmetic Packaging to Save the Environment: Future Perspectives. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 26.

[7] Rosenow, P.; Destler, E.; Springer, A. The Search for Suitable Packaging for Cosmetics – a Case Study. SOFW Journal 2022, 148, 56-59

[8] Amberg, N.; Magda, R., (2018), Environmental Pollution and Sustainability or the Impact of the Environmentally Conscious Measures of International Cosmetic Companies on Purchasing Organic Cosmetics, Visegrad Journal on Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development, 7(1) : 23-30

[9] Amberg, N.; Fogarassy, C. (2019), Green Consumer Behavior in the Cosmetics Market Resources, Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 8, 137

[10] Martins, A.M.; Marto, J.M. (2023), A sustainable life cycle for cosmetics: From design and development to post-use phase, Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy Volume 35, October 2023, 101178

[11] Rosenow, P.; Destler, E.; Springer, A. The Search for Suitable Packaging for Cosmetics – a Case Study. SOFW Journal 2022, 148, 56-59

[12] Filiciotto, L.; Rothenberg, G. Biodegradable Plastics: Standards, Policies, and Impacts. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 56–72

[13] Yu, C., & Anigbogu, C. (2020). How waterless beauty is changing consumer behavior and addressing sustainability. Cosmetics & Toiletries, 135(9), 51-52

[14] Williams, J.H; Jones, R.A.; Haley, B.; Kwok, G.; Hargreaves, J.; Farbes, J.; Torn, M. S. Carbon-Neutral Pathways for the United States. AGU Advances 2021, 2, e2020AV000284.

[15] European Commission (2022), Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on packaging and packaging waste, amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904, and repealing Directive 94/62/EC

[16] Morel, S.; Mura, G.; Gallarate, M.; Sapino, S. (2024), Cosmetic Packaging: European Regulatory Aspects and Sustainability, Cosmetics 2024, 11(4), 110

[17] Fortunati, S.; Martiniello, L.; Morea, D. (2020), The Strategic Role of the Corporate Social Responsibility and Circular Economy in the Cosmetic Industry, Sustainability 2020, 12(12), 5120

[18] Kassaye, W.W. Green Dilemma Marketing Intelligence and Planning 2001, 196, 444–455

[19] Mäkiä, E. (2021), How Cosmetics Companies Can Improve the Credibility of Green Marketing – A Consumer Perspective, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

[20] Bratt, C. Consumers’ Environmental Behavior: Generalized, Sector-Based, or Compensatory?. Environment and Behavior 1999, 31(1), 28–44

[21] UNEP. Biodegradable Plastics and Marine Litter. Misconceptions, concerns, and impacts on marine environments. Publisher: United Nations Environment Program, Nairobi, Kenya, 2015

[22] Karwowsky, M.; Raulinajtys-Grzybek, M. The application of corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions for mitigation of environmental, social, corporate governance (ESG) and reputational risk in integrated reports. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2021, 28, 1270–1284

[23] Bozza, A.; Campi, C.; Garelli, S.; Ugazio, E.; Battagila, L. Current regulatory and market frameworks in green cosmetics: The role of certification Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2022, 30, 100851.